William Robert BRIGGS

TYNESIDE Z/9805, Able Seaman, b. 2nd March 1898, Bradford d. Wed. 12th December 1917 (aged 19).

William (known as Robert) was the eldest son of William and Laura Agnetha Briggs of 6 Beech Grove, Clayton, his father William being a former well known local newsagent. Robert was a bright boy and was assistant gardener to Mrs. Asa Briggs of Oakdene, Clayton. [From Bradford Observer, Roll of Honour 5th February 1917].

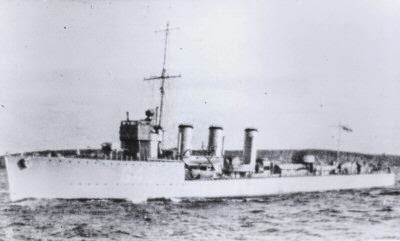

Robert had been sworn into the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on the 2nd June 1916 and after training as a fire corporal, Robert was posted to the H.M.S. Partridge on 4th November 1916, a small warship patrolling the waters around the British coast. The previous H.M.S. Partridge had been lost in the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, and William’s ship was launched on 4th March 1916 with a crew of 80.

HMS Partridge was a part of the 14th Destroyer Flotilla based at Scapa Flow, the Navy’s huge anchorage in the Orkneys and was being used to escort convoys to and from Norway.

Convoy

On 11 December 1917 HMS Partridge was part of the escort of a small convoy of merchant ships crossing from Lerwick to Bergen in Norway. Leading the convoy was HMS Pellew (a sister ship of Partridge) and, together with four armed trawlers these navy ships formed the escort for six merchantmen; Bollsta and KongMagnus (Norwegian) Torleif and Bothnia (Swedish), Maracaibo (Danish) and Cordova (British) sailed from Lerwick, due to reach Bergen, around noon on 12 December.

The convoy was escorted by the destroyers HMS Pellew, Partridge and the Admiralty trawlers HMT Livingstone, Commander Fullerton, Lord Alverstone and Tokio.

Convoy attacked

At 11.45am on 12 December the convoy was attacked by four German destroyers, all larger and better armed than the Pellew and Partridge. The Partridge was the first to be hit by a shell that cut her main steam pipe and left her dead in the water. She did fire a torpedo that hit one of the German destroyers, but failed to explode. She was then hit by a torpedo and the commander, Lt Cdr Reginald Hugh Ransome, gave the order to abandon ship; two further torpedo strikes finished her off and she sank with most of the crew still on board. The Germans also hit the Pellew forcing her out of the action and then proceeded to sink all four trawlers and the six merchantmen (allowing their crews to abandon their ships before they were sunk).

This was the second convoy lost to attacks by surface ships that year (the previous being on 17th October) and highlighted the weakness of the convoy protection, which was only designed to counter the U-boat threat. Subsequent convoys were sent with stronger escorts and the next German attack, early in 1918, failed – they never tried again.

Losses

Although initial reports were that the Partridge went down with all hands it was subsequently discovered that 3 officers and 21 ratings had survived – but 5 officers and 92 ratings did not.

On 17th December 1917 William Briggs received a letter from the Admiralty giving the news that Robert who had been serving aboard is reported to be missing. In addition it states that three officers and 21 members of crew were taken prisoner and had landed in Germany on the 15th December and that further notification would be sent once the names of the survivors are known.

On 26th January 1918 William Briggs received the sad news that his son was not one of the survivors listed on PoW lists received from German authorities via International Red Cross in Geneva.

I suspect that this news did not come as a complete shock for Roberts parents as during the intervening period Roberts parents and those of the other crew were desperate for information and had written letters to families of crew members seeking any information from survivors who may know or have seen their missing sons. One father, William Handley had received news from his son who was interned in a POW camp, and Roberts parents asked if he would enquire if his son had seen Robert. His son was able to relate that “Robert was in the fire control cabin under the Bridge, when a salvo blew everything over side, so can safely say was lost.”

Photo of Partridge being hit

Survivor account

Among the survivors from the Partridge was John Bradley, an Engine Room Artificer (ERA) who later gave this account:

1917 Dec.12 I had the afternoon watch. At 11.50 the bell rang for Action Stations and we left our dinners and went below. Just about 12 o’clock firing started and by about 12.15 we had the H. P. Steam pipe shot away and the turbines stopped. At the same time the Port Turbine got smashed up. We were then ordered to leave the Engine Room. As the last man was leaving the Dynamo got hit.

We got the midships raft into the water and put life belts on. I had one that someone else threw down. It had the white tape tied to the Blue. We went into the ditch at 12.20. It didn’t seem too cold until we had been in the water for a time. We then pulled towards the German T.B. who picked us up. They let us dry our clothes in the Engine Room and gave us some rye bread and raw bacon to eat. Most of us went forward to sleep at night. I was in the foremost bunk and didn’t sleep much.

This was the second convoy lost to attacks by surface ships that year (the previous being on 17 October) and highlighted the weakness of the convoy protection, which was only designed to counter the U-boat threat. Subsequent convoys were sent with stronger escorts and the next German attack, early in 1918, failed – they never tried again.

HMS Partridge (1918)

In a true ‘phoenix from the ashes’ story, within months a ‘new’ H.M.S. Partridge III had been built in the shipyards of Southampton and she was officially launched in April 1918. This boat managed to take revenge for its forebear’s demise by sinking a U-boat in the English Channel on one of its very first missions in early June: perhaps the fact that another H.M.S. Partridge saw service throughout World War II gives a sense that the legacy left by Roberts ship was being continued.

A curious fact to note is that although Robert served in the Navy he could not swim at time of enlisting swim, according to his official enlistment papers.

Roberts name is inscribed on the Chatham Naval Memorial.

Photos of HMS Partridge crew

Acknowledgements and additional material

Margaret Parker (née Margaret Briggs) has Roberts scrapbook passed down, as Robert was Margaret’s Uncle. The book contains amongst Roberts own drawings and stickers, letters from Admiralty, friends of Robert and communications from The King, as well as cuttings from the papers of the day relating to the sinking of the Partridge and the photographs above. Thankyou Margaret for sharing this precious family heirloom.

Heroic actions of Officer Lieutenant Aubrey Grey aboard HMS Partridge

From a Sunday Telegraph article in 2013, related by the son of Lt Aubrey Grey, one of the officers aboard HMS Partridge:

As their ship sank in icy waters off the Norwegian coast, two Royal Navy officers found themselves in rough conditions a quarter of a mile from a life raft, their only apparent prospect of survival.

One of them, Lt Launcelot Walters, was exhausted and close to drowning so had to be helped by the other, Lt Aubrey Grey, who, although wounded, was the stronger swimmer.

When the pair reached the raft, however, they found room enough only for one on board. Grey insisted his exhausted comrade Walters take the final spot, while he swam off, his fate seemingly sealed.

In the event, only one of the men lived. But in a twist of fate, it was Grey who survived, when he was picked up by one of the German ships which had sunk their vessel, while Walters was never rescued.

This remarkable tale of heroism is one of many to have emerged after an appeal by The Sunday Telegraph for readers to contact us with their stories about the First World War.

He was a lieutenant on HMS Partridge, a destroyer, when it left Lerwick, on the Shetland Islands, on Dec 11 1917, along with another destroyer, HMS Pellew, and four armed trawlers, to escort six merchant ships, bound for Bergen, in southern Norway.

A flotilla of four German warships – G101, G103, G104, and V100, under Lt Commander Kolbe — had been searching for just such a convoy and sighted the vessels off the Norwegian coast at around midday the following day.

The crew of the Partridge spotted the German vessels on the horizon, but could not make out whether they were friend or foe and due to a defective searchlight, they were unable to make a challenge for about 10 minutes. The delay allowed the enemy to close in.

Once the ships were close enough to identify, the merchant fleet were ordered to scatter and the Partridge attacked the German vessels. A torpedo hit one of the vessels, but it failed to explode and, outnumbered and outgunned, the Partridge was repeatedly hit by shells and torpedoes. One of the first salvoes had hit the ship’s high-pressure steam pipe, meaning it could no longer move. Subsequent hits put some of her guns out of action.

The captain, Lt Commander Reginald Ransome, gave the order to abandon ship, just before the vessel went down, around 40 miles from the Norwegian shore. The only other Royal Navy destroyer, HMS Pellew, was able to escape, but the German fleet proceeded to sink every other vessel in the convoy.

As they did so, Grey and Walters, the 22-year-old son of a vicar, from Castle Bromwich, in the West Midlands, were in the water and fighting for their lives. An account of the battle says that while the ship was being evacuated, the two men had stayed at their posts, manning the torpedo tubes, to allow as many men as possible a chance of escaping.

Grey had been wounded in the thigh by shrapnel during the fighting and was placed in a life boat with many others. This capsized, throwing all the occupants into the water. Despite his injury, Grey helped Walters, who had also ended up in the water, to swim towards one of the Carley Float life rafts.

When they realised there was only room for one, Grey insisted it be his comrade. After that, he swam for around half-an-hour towards one of the vessels, blood flowing freely from his leg wound, before he was spotted by the crew of the V100. After three unsuccessful attempts he was finally hauled aboard, where he fell unconscious. He spent the rest of the war as a prisoner at Kiel, on Germany’s Baltic coast. He had been one of only 24 of the crew of the Partridge to have survived. Reports indicate that 97 were killed.

After the war, he was awarded the Stanhope Gold Medal by the Royal Humane Society, a charity which promotes lifesaving.

The medal was introduced in 1873 and was first awarded to Captain Matthew Webb, the first man to swim across the channel, after he attempted to rescue a sailor who had fallen from the rigging of a ship into the Atlantic Ocean. Webb swam for more than half an hour but found only the man’s cap.

Mr Grey said he had learnt of his father’s exploits from his mother and that his father had not liked to talk about it. He did not see the medal until 1948 when his father wore it when he passed out from Sandhurst, the military college.

“My mother had made him wear it. But even then, he didn’t really speak about it. People back then just didn’t seem to like talking about their experiences. I am very proud of what he did.”

The HMS Partridge incident is referred to on a small plaque in a church in Stoke Climsland, Cornwall, where Walters’s father, Rev Charles Walters, was based during the war. Mr Grey was recently contacted by the congregation, who were keen to learn the full story.

Mr Grey recalled that his father later befriended a German sailor, Friedrich Ruge, who had been on the V100, which was involved in the sinking of the Partridge and rescued him, after the pair met during a regatta on the south coast in the 1930s.

The two men corresponded until the outbreak of the Second World War, and then continued their friendship after the war, during which Ruge rose to the rank of Vice Admiral, and served as naval adviser to Erwin Rommel.

Ruge continued to serve in the German navy when his country joined Nato and, in 1962, he appeared as himself in The Longest Day, the D-Day film. Grey, who was also a keen motor racer, had remained in the navy and also served during the war, designing torpedos. He died, aged 84, in 1979.

Links to resourses

Musings from Higher Downgate and Elsewhere: An overlooked deed of WW1 bravery